DAVID ANDREATTA

From Saturday’s Globe and Mail

PublishedÂ

When Nigel Bart decided that his experience reining in his demons made him ideally suited to fill a counsellor opening at a Winnipeg public mental health agency, it had been seven years since he had been tormented by the voices in his head.

That he was a local man with a university degree and a passion for mental health issues had him sailing through the interview, he recalled – until he mentioned his schizophrenia.

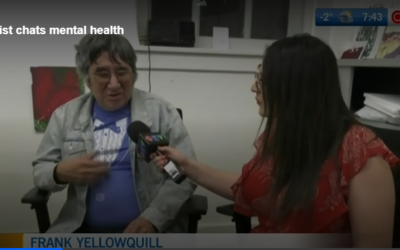

“I could see them just brace themselves a little bit,” said Mr. Bart, 32, an artist who now runs a studio to benefit mentally ill artists.

“They called me later to tell me that I didn’t get the job and when I asked them why, they said it was because I made an unhealthy disclosure. That’s what they called it.”

For those with mental illness, there is often a price for coming out of the shadows. Promising job prospects turn bleak. Friendships go sour.

But in much the same way that members of other minority groups historically marginalized by society organized to fight for and win better treatment and more government protections, the mentally ill and their families are scoring victories as their own lobby.

The most recent of these, advocates say, is the creation of the federal Mental Health Commission of Canada, whose primary purpose is to develop a national strategy to combat mental illness and the stigma attached to it. Its chairman, former Liberal senator Michael Kirby, and five of its 17 board members either live with mental illness or have a close relative who is a sufferer.

“This is the first time ever that there has been a national focus on mental health in this country,” Mr. Kirby said in a telephone interview. “We’ve got to make absolutely sure that we prevent this issue from ever going back into the shadows.”

To that end, the commission is considering a slew of initiatives aimed at going beyond the traditionally staid public service ads and changing the way services are delivered to the mentally ill.

One of those is the creation of federally funded affordable housing units for the mentally ill. Advocates envision entire communities where residents can find services and support groups, including peer interventions, at their fingertips within their development, rather than having to bounce between a hodgepodge of hospitals and clinics.

There are also calls for changes to the Criminal Code that would grant review boards the same power as the court system to order the involuntary treatment of mentally ill people in the justice system.

But in pushing for change, Mr. Kirby and his colleagues on the commission face a tough battle. Although government statistics show that roughly 15 per cent of the population suffers from at least a moderate mental illness, such as depression or anxiety, government services fall woefully short of demand.

Provinces have laws to protect people with disabilities, but none explicitly address mental illness, advocates say. Services are limited in many parts of the country, and only those provided by doctors or through hospitals must be publicly funded. A $300-million federal health promotion prevention fund established in 2005 allocates less than 2 per cent to mental health.

The short shrift, advocates charge, is fuelled by indifference toward the mentally ill across all segments of society, including at the highest levels of government.

“I’m not sure it can be eradicated any more than racism can be eradicated,” said Phil Upshall, national executive director of the Mood Disorders Society of Canada and an adviser to the commission. “What we can do is develop human rights for people with mental illness the same way we’ve done for people with physical disabilities. Attitudes have to change.”

The commission is considering adopting a tactic used in Australia, where mental health education is mandated in Grade 5. Students are introduced to everyday people with mental illness, to show them that sufferers can live productive and normal lives.

Such a strategy might help relieve the anxiety faced by children like Erynn Quigley. The 11-year-old sixth-grader began exhibiting symptoms of bipolar disorder as a toddler, and today ingests a cocktail of five different medications to control mood swings ranging from seething rages to manic highs.

The disorder has made her the subject of name-calling and cruel horseplay. She is acutely aware of how her illness is perceived by others.

“I want people to know that bipolar disorder doesn’t make you different from anyone else, but I’m afraid people will run away from me at school because they’re afraid I’ll have a mood swing,” she said.

The federal panel is not expected to have a definitive plan of action for its anticipated $5-million, decade-long anti-stigma campaign until next spring.

Changing attitudes is the driving force behind Artbeat Studio in Winnipeg. The studio, founded by Mr. Bart after the Winnipeg public mental health agency rejected his application as a counsellor on the basis of his schizophrenia, aims to reintegrate mentally ill artists into mainstream society.

Thirteen years ago, the paranoid delusions that had sent Mr. Bart on all-night scavenger hunts around Winnipeg for signs from God paralyzed him in the library at the University of Winnipeg, where he was a student. A librarian found him curled up under a cubicle.

After a year of recovery on his parents’ farm that included sleeping for months on end, therapy sessions with a psychiatrist and adjusting to medication, he enrolled in art school at the University of Manitoba, where he eventually earned a bachelor’s degree.

Now happily married and a father to a young son, Mr. Bart still takes medication daily and has made educating the public about mental illness his mission. He has not had a schizophrenic episode in four years.

“Recovery does not mean cure,” he said. “I may very well be taking medication for the rest of my life. But what needs to be understood is that people with mental illness can achieve great things.”