Opportunities allow creators’ skill, not their illness, speak first

BY JONATHAN FORANI, FOR POSTMEDIA NEWSÂ JANUARY 20, 2014

Lucille Bart, Executive Director, and her son Nigel Bart, studio facilitator and founder of Artbeat Studio are photographed with the art of Kyla Jane Betker and Joseph Harlow at the opening of an exhibition called “Querencia” in Winnipeg Friday, January 17, 2014. Artbeat Studio is a family-run studio in Winnipeg for artists with mental health issues.

Photograph by: John Woods, National Post

When Nigel Bart was 18, instead of facing the exciting prospects of adulthood, he faced a diagnosis of schizophrenia.

He left university and the study of sciences. He stayed in bed for days, never rested. Always an artistic person, he had lost the desire to create. There was no respite from the symptoms of his illness.

“I was trapped in my mind, and it wasn’t a pleasant place to be,” Bart recalls.

But he soon found recovery in a surprising place: his mother Lucille’s pottery studio.

There, he could begin his recovery journey. In the next year, Bart began a degree in fine arts at the University of Manitoba, and began volunteering in the mental health sector, meeting other creative people with mental illnesses.

“When I started expressing myself through art, I was able to regain control of the insanity,” says Bart, now 38. “I’ve come to a point in my life where I’m not conscious of my illness all the time. When I do artwork it’s about other things – it’s about love, it’s about death, it’s about living.”

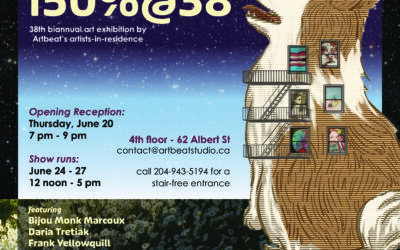

Like many unsung artists across Canada, Bart is finding relief and inspiration in the creative process. Now, he’s investing in the recovery of others, too. In 2005, Bart and his parents started Artbeat Studio, where artists find healing and empowerment in their work.

But an unexpected success came out of Bart’s studio and many like it across Canada. The social stigma attached with mental illness – a sad truth, despite the fact that it is something 20 per cent of Canadians will experience in their lifetime – could be fought with art.

Nigel Bart, studio facilitator and founder of Artbeat Studio, is photographed with art by Kyla Jane Betker at the opening of an exhibition called “Querencia” in Winnipeg Friday, January 17, 2014. Artbeat Studio is a family-run studio in Winnipeg for artists with mental health issues.

Photograph by: John Woods, National Post

Every six months, a new group of nine artists take over the downtown Winnipeg studio. At the end of the program, they present their work in a public exhibition. The goal? To see the kind of recovery Bart has seen himself.

The small Winnipeg studio is not alone in its creative advocacy. At St. Anne’s Parish Hall in Toronto, some 250 artists with mental illness develop their craft each year through classes and exhibitions in Lisa Brown’s Workman Arts group in partnership with the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health.

Like Artbeat, though the work may be therapeutic, it’s not “art therapy.” These are real artists honing their craft.

So much so that Brown invests in their finished work. If the walls of her Little Italy home could talk, they’d be muffled by the stories of the artwork hanging on them. Since the late ’90s, she has been purchasing work by the artists in her program. Brown doesn’t hang the artwork because it matches her walls. In fact, she painted her dining room nine times to fit the shade of one of her favourite selections, a painting by former Workman member and award-winning artist Peter Smith, who died just months before he was set to open a show at the National Gallery.

What’s most important for Brown is that the skill of the artist speaks first, not the mental illness.

It’s a mistake to consider people who come out of a mental institution as amateurs, says Brown, who started the non-profit initiative as a nurse at Queen Street Mental Health Centre in 1987. “I think that despite a mental illness, you can still create art, and it can be as big and as beautiful as if you didn’t have a mental illness.”

Melissa Bender, 35, is a Workman Arts member and a graduate of the Ontario College of Art and Design, where many of Workman’s members have trained.

“There is a huge stigma still connected to admitting that you have a mental illness,” says Bender, whose battle with anxiety and depression features greatly in her drawings. “Art doesn’t erase that, but it just seems to be a bigger heading on top of that. There’s a lot of power in that. Not just in how other people see you, but how you see yourself.”

For artist and University of British Columbia psychology professor Steven Barnes, 40, branching back out into the art world after an extended foray into neuroscience helped him find stability in his life. Barnes has bipolar disorder, but has found stability as a collective member at Gallery Gachet, an artist-run centre in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside.

“Since the time I joined the gallery I’ve had quite a few showings, and it’s been very encouraging. It helped me build self-confidence. It’s taken me from a place where I was functioning to a place where I’m approaching a higher level of functioning than I have had for quite some time.”

Barnes, an oil painter and new media artist, is considering starting a course in UBC’s psychology department on the relationship between madness and creativity, a link that many in the sciences continue to grapple with.

“This adage that you have to be mad to create is something that no one’s going to solve, I think, ever,” says Workman founder Brown. “What I think will come through is that art is a portal into the mind and art can help express inner thoughts, demons and ideas.”

It may be many decades still before some quantified understanding of mental health in the arts is formed. For now, the pottery of Lucille Bart, matriarch of Winnipeg’s Artbeat Studio, offers a simple metaphor for what really matters.

In a Japanese technique called raku, the pots are heated with a propane torch, reaching extreme temperatures of about 1,000 C before they are cooled in a container and doused with cold water.

“Because of the thermal shock, there’s high risk involved for cracking and shattering. But on the other hand, the pieces are just so beautiful and the flaws enhance it. It’s just like people,” she says, noting her son’s recovery journey with schizophrenia. “It makes us stronger in the end. Even with our imperfections and our scars, we’re beautiful.”

Next week: From van Gogh to Cobain, a look at the theory of the “mad genius.”