Alumnus Jamie Hogaboam

Homelessness in Winnipeg: A day in the life

MyToba.ca | April 2015 | Ryan Bowman

This is the fifth article in a seven-part series exploring the state of homelessness in Winnipeg. Watch for Part 6, which will look at the concept of housing first, on Saturday.

Jamie Hogaboam will be the first to admit he’s led a life of disorder and instability.

For the majority of his adulthood, the 50-year-old artist has bounced around from city to city, endured a parade of low-paying and unfulfilling jobs, struggled with an erratic gambling addiction and battled situational depression.

But even when the chaos got to the point that Hogaboam had to quit his job, he never imagined he would end up sleeping on the streets or living out of a homeless shelter. In November 2014, it became his reality.

“You never really think it will happen to you, you never think you’ll end up like this,†says Hogaboam, who stays at the Siloam Mission. “Nobody does. Then it happens and you realize it can truly happen to anyone.â€

The 110-bed emergency shelter at Siloam Mission, where Jamie Hogaboam has been staying since November 2014.

While it is generally accepted among social services circles that there are between 2,500 and 3,000 people living on the street, in shelters or in temporary accommodations at any given time, many of them go through life largely unnoticed and largely ignored.

But just because people don’t see them, Hogaboam says, doesn’t mean they don’t have a voice.

“My story, the story of all homeless people, is a story that needs to be told,†he says. “I want to tell my story.â€

Hogaboam’s story begins in California, where he was born to a young couple who had traveled south from Manitoba in an attempt to cash in on the state’s economic boom in the 1960s.

Before Hogaboam was a year old, however, his father had a stroke and the family moved back to Winnipeg. His father died shortly thereafter. His mother collected welfare until she was able to land jobs at retail giants like Eaton’s and Sears.

Hogaboam’s teenage years were, by and large, uneventful. He cruised through high school with straight As and developed an interest in music.

“I was never very good, but I looked the part,†laughs Hogaboam, a big man with kind blue eyes and longish gray hair. “It was the 80s and I could go to the bar and everyone would think I was in Motely Cru or whatever, with the hair and the makeup. It was great.â€

Following high school, Hogaboam spent a semester studying computers at the University of Winnipeg and another semester studying electronic technology at Red River College before deciding the tech sector wasn’t for him. After giving up on any kind of music career and having his heart broken by a girl, he moved to Alberta, where he graduated with a diploma in broadcast journalism.

After a few years of spinning country records, broadcasting minor hockey games, selling media ads and launching a weekly newspaper featuring local athletes, he yearned for some stability and moved back to Winnipeg.

“At this point I’m in my early 30s and I want some kind of a life. I want to have a meaningful job, I want to have a family,†Hogaboam recalls. “But so far it’s just been crappy temporary jobs, moving back and forth. It just isn’t working for me.â€

Meanwhile, his mother had died and he was struggling to get by – both financially and emotionally. While he worked a day job as a courier, he had also begun experimenting more with his artistic inclinations and taken a serious interest in painting.

As the bills began to pile up, however, he devoted less and less time to his art and took a job as a taxi driver, working up to 12 hours a day, seven days a week.

“I went to work, I came home and paid the bills. That’s all I did,†he says. “For me to save enough for a down payment on a house, I’m looking at another 20 years of this.

“Meanwhile, people are telling me I have great artwork, but I don’t have any time to work on it.â€

One day the stress got to Hogaboam and he hit a wall. He quit his job and, as he tended to do when things got tough, began to gamble. Within a week, he had blown through his entire $4,000 of savings.

“It all fell to pieces,†he says. “And it all came down to this life that I wanted that I didn’t have.â€

History repeats itself

Seeking a reprieve from the high stress and daily demands of city living, Hogaboam moved to the Victoria Beach area north of Winnipeg, where he scratched out a living and dedicated more time to his art.

After five years, feeling inspired and refreshed, he decided to move back to Winnipeg. He took on a courier job and continued painting in his spare time. For a while things were good.

Then the recession hit. Earnings went down and rent went up. Scrambling for some financial stability, he took up residence with a series of roommates, but nothing stuck. Again, he got to the point of working 80-hour weeks and barely getting by.

He looked for other jobs but had no luck. Depressed, he spent his days driving around the city and his evenings curled up on the couch. Then arrived the inevitable day he knew was coming but had been trying to delay.

“There was one stormy day I was out delivering flowers,†he says. “Because of all the snow and the ice and the bad weather, I only made eight deliveries that day. I was getting $6 a delivery. And I went through $45 worth of gasoline.â€

Again, he quit his job. Again, he gambled away his savings. Again, he was evicted. Again he said goodbye to the city and sought reprieve in the north. Again, he recharged his emotional battery before returning to Winnipeg.

This time, however, he had nowhere to go.

He could have found another minimum wage job and climbed back on the hamster wheel, he knew, but he didn’t want to recycle the vicious cycle that had become his life.

“I was fed up,†he said. “I didn’t know what to do, but I knew I couldn’t go back to the way things were.â€

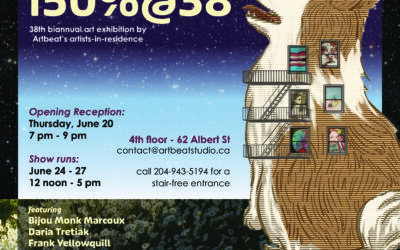

While living with a friend, Hogaboam met one day with Lucille Bart, the executive director of Artbeat Studio, whom he knew from his time as a resident with the studio’s art program. Fresh off a grant from the Downtown Winnipeg BIZ, Bart was in the process of opening Upbeat Artworks, a boutique gallery in Portage Place featuring the work of local artists. She asked Hogaboam if he would be interested in displaying his work – and also if he would like a job.

While it was part-time and only paid about $250 a month, Hogaboam accepted. It was better than nothing. And it was – for a change – something he was passionate about.

When his welcome on his friend’s couch ran out, however, he found himself low on money and low on options. At the age of 50, he spent his first night sleeping on the street.

“All I have is a backpack, and I’m sleeping outside,†he says. “It’s cold and it’s scary and I have no idea what I’m doing.â€

On the recommendation of another artist he met on the street, Hogaboam lined up at the Siloam Mission. On the second day, he got a bed.

One of his first days at the mission coincided with an art fundraiser at the Fort Garry Hotel featuring some of his work. He dressed in his nicest clothes, walked over to the hotel and enjoyed the last decent meal he can remember.

“Here I am, a homeless guy getting hugs from Margaret Trudeau,†Hogaboam says, shaking his head. “And no one would ever know it.â€

An education

A day in the life of Jamie Hogaboam begins at 6 a.m.

He showers, selects an outfit from his slim selection of clothing – usually a pair of tan cargo pants and a long-sleeved t-shirt – and slips on his bulky weathered boots.

He joins the shelter’s other residents for breakfast on the main floor of the Siloam Mission, eating enough to hold him over until the next meal.

Then, most days, he will walk the 1.6 kilometres to Studio Central, where he will lose himself in a canvas and paint the day away. Once or twice a week he will continue a couple of blocks farther to Upbeat Artworks, where he will work a four-hour shift in the gallery.

Before returning to Siloam for dinner, he may or may not spend a few hours pandhandling downtown. “It depends on my mood and the weather,†he says.

He spends his evenings reading or socializing with newly-acquired friends at the shelter before turning in around 10 p.m.

The daily routine is a world away from what a young and ambitious Jamie Hogaboam would have imagined for himself, but it has become reality.

Hogaboam says the experience has been both humbling and eye-opening.

“When I first got to the shelter I was scared,†he admits. “I didn’t know who I’d be living with. Like a lot of people, I thought they were all alcoholics, drug addicts, gang members, or just lazy. Even when I heard stories on the news about mental illness and that, it didn’t click that these people might be normal.

“But after five months of living with these people, who are supposedly the lowest of the low, I started to realize that a lot of them were just like me. They’re smart and they’re talented and they’re nice,†he says. “They have plenty of hurdles to overcome, but they’re still trying. They’re not bums, they’re not lazy, they’re not what people perceive. The majority of them either have mental health issues or they’ve fallen down.â€

All a lot of homeless people need, Hogaboam says, is a hand getting back up.

“We need help and support, and somewhere to live,†he says. “We can be functioning members of society, but we need some support. And we shouldn’t have to beg for it.â€

The shame game

Whether it be walking down the street or sitting at a corner with a cardboard sign and a paper cup, Hogaboam says he has experienced insults, sneers and straight up abuse since becoming homeless.

As judgmental as others can be, however, he says nothing can compete with the shame he cast on himself those first few days on the streets. No one ever thinks they’ll end up homeless, he says, so when they do it is “embarrassing and degrading.â€

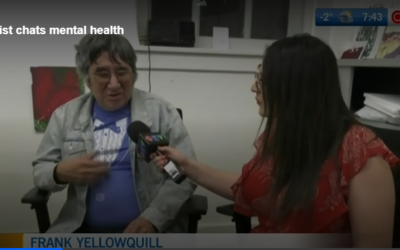

“When I first went on the street to panhandle, I had a sign that said I have a mental illness and that I’m homeless,†he says. “I really felt ashamed to be telling people that I was homeless and that I was depressed.â€

But over time, Hogaboam has begun taking offence to the prejudice and discrimination. It’s not so much that he takes it personally, he says, but that he now understands how wrong the public’s perceptions of homeless people are.

“People walk by me and give a rude look or say something, but they don’t get it,†he says, “and that used to be me.

“People think anybody asking for money on the street wants to buy a case of beer or their next hit. I don’t do drugs, I don’t drink. I do like to have a burger once in a while, and maybe one day I can save enough to get an apartment and not have to worry about ending up where I was a year ago.â€

Floyd Perras, the executive director of Siloam Mission, says this misconception of homelessness is all too common. And that it couldn’t be further from the truth.

“People will look at a 30-year-old male or a 40-year-old male and say, ‘I don’t see any reason why that guy couldn’t have a job,’†Perras says. “The reality is, that person might have fetal alcohol syndrome and they don’t have the impulse control to manage employment or social relationships.â€

“The truth is, 20 or 30 of these guys get up early every morning and go to the temp services,†he says of the residents at Siloam Mission, which has 110 beds. “And most of the people who aren’t working want to be.â€

Brian Bechtel of the Winnipeg Poverty Reduction Council says this “shaming and blaming†is not only a lazy way of thinking, but it also perpetuates homelessness. People who fear judgment and blame, he says, tend to avoid reaching out for services and support.

“If we’re really going to end homelessness, we have to suspend that whole conversation about whose fault it is and who’s to blame. That’s what blocks us from finding the solution,†he says.

“I don’t want to get too philosophical, but until you’ve really seen some of the circumstances and lives of these people, who came out of the gate with two strikes against them, whether it be family or health, it’s hard to judge,†he adds. “I had a pretty easy path and I can’t honestly say I would do any better if I’d had some of those circumstances.â€

Beggars and choosers

When it comes to debates about homelessness, none is greater than the question of whether or not living on the streets is a choice.

While Hogaboam concedes that, technically, some people may be choosing the lesser of two evils, nobody actually wants to be homeless.

Yes, he could get a minimum wage job. Yes, he could live in a substandard apartment. Yes, he could go back to the life that landed him on the streets.

But just because somebody is marginalized or at risk, Hogaboam says, doesn’t mean they should have to settle. He believes that all people should have a right to housing, but also that it shouldn’t come at the expense of their dreams and ambitions.

It may seem to others that he is choosing to be homeless, Hogaboam says, but what he is really choosing is to be happy.

“I can go back to living the way I was and have a job and a home, but I would rather have no money and be homeless and devote my time to my art. That’s what I want out of life, even if it means living in the mission.

“It took me a long time to realize that what you want out of life is not what 99 per cent of the other people want out of life,†he adds. “Sure, my life can be chaotic, and I get frustrated sometimes, because I want to be off the streets. But not at the price of going back to the way I used to live.â€

Floyd Perras chuckles as he talks about people rifling through the Siloam Mission’s clothing bank.

“You’d think because they’re homeless they wouldn’t be picky, but they’re like anyone else,†he says. According to Perras, people will sift through the piles and racks of clothing like a shopper would in a store, looking for brand names and ensuring things fit just right. “It shows they still care about how they’re perceived and want to feel good about themselves.

“Sometimes we think, ‘Shouldn’t they just take what they can get?’ The truth is, they want to choose their own clothes, they want to have enough for coffee or eating out the odd meal. A lot of them even have cellphones.â€

Brian Bechtel says this kind of thing serves as a necessary reminder that homeless people are really just people who are homeless. They have the same emotions, feelings, fears, desires, hopes, ambitions, anxieties and dreams as anyone else.

“The humanity that I see on the streets every day is something that continues to surprise me, even though I know it shouldn’t,†Bechtel says. He brings up the example of Faron Hall, known in Winnipeg as the “homeless hero†for saving at least two individuals from drowning in the Red River, the very river that took Hall’s life last summer.

“People are surprised a homeless guy actually cared,†Bechtel says. “Of course he did. It shouldn’t surprise people that he’d be just as motivated to save someone from drowning as anyone else.â€

And it shouldn’t surprise people that despite his experiences, Hogaboam still has hope.

“I had to get through the feeling of worthlessness, the feeling that I’m nothing,†he says. “But now that I’ve been on the street for five months, I feel like I’ve gotten through the worst of it. There are still emotional struggles, but I have to tell myself there’s a reason for it all.â€

— RYAN BOWMAN, MyToba.ca

To check out some of Jamie Hogaboam’s art, visit his Facebook page.

This is the fifth article in a seven-part series exploring the state of homelessness in Winnipeg. Watch for Part 6, which will look at the concept of housing first, on Saturday. [hr]